By Maj. William Carraway

Historian,

Georgia National Guard

|

| The 121st distinctive unit crest, map of Normandy, after action report and modern image of Hill 112. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

On July 4, the first Soldiers of the Georgia National

Guard’s 121st Infantry Regiment splashed ashore on Utah Beach as part of the

8th Infantry Division.[1] Leaving their landing

crafts, the troops marched 22 miles to an assembly area near Montebourg, north

of Ste. Mere Eglise. The march was conducted in full combat gear in one of the

hottest Julys on record. The march to, and assembly area in Montebourg,

afforded the Soldiers their first view of the bocage country which would define

their combat conditions for the next several weeks. The bocage consisted of

open fields bordered by woodland and tangled natural walls of vegetation,

perfect for the design of the defense. For weeks, allied forces had struggled

to drive German defenders from behind the natural bulwarks of the bocage.

|

| The 121st Infantry assembly area in the bocage country near Montebourg, France. Photo by Maj William Carraway |

From Montebourg, the 121st was dispatched south to La

Haye du Puits, where the U.S. VIII Corps was attempting to dislodge German

forces and advance out of the swampy lowland terrain. The town stood athwart a crossroads

that served as a key route of advance south for the American advance. South of

Le Haye du Puits was the town of Lessay near the mouth of the Ay River. Ten

kilometers to the east of Lessay lay the town of Periers. Three American divisions,

the 79th, 82nd Airborne and 90th, had thus far been unable to effect a

penetration of German lines and establish a crossing of the Ay. Arriving on

July 8, the 8th Infantry Division was assigned as the main effort of the attack

which would strike south from the east of La Haye du Puit and drive between

Lessay and Periers.[2]

|

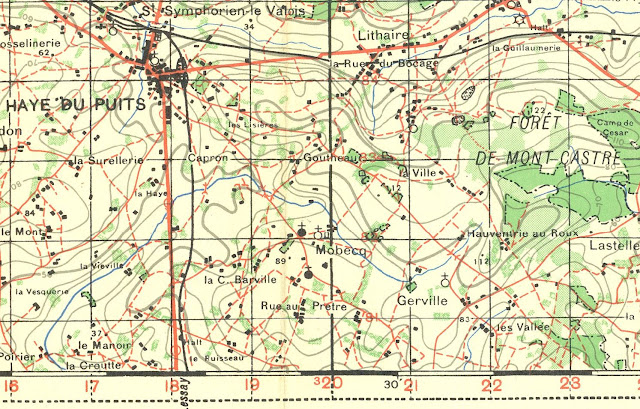

| 1942 map showing La Haye du Puits and vicinity. Hill 112 can been just west of the 22 line below Haventrie au Roux. |

The next morning, the 121st assaulted German positions

east of La Haye du Puits from the northeast moving out under cover of

artillery. With Lt. Col. Burton Morrison’s 2nd Battalion in the lead, the Soldiers

advanced approximately 500 yards with 1st Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col.

Robert Jones, following in support. In short order, 1st Battalion began taking

fire on their right flank from La Haye du Puits. Withering German machine gun

fire raked the 121st while mortar fire and machine gun fire from the front stopped

the advance. The 1st Battalion, in the vicinity of Hill 95, found itself in a

particularly desperate situation with elements of Company A temporarily

isolated. By 5:30 that evening, elements of 3rd Battalion, supported by tank

destroyers, were sent in to support 1st Battalion. Meanwhile, Soldiers of the

2nd Battalion were decisively engaged with Company G taking 30 percent casualties.

Though outnumbered, the German infantry was well entrenched in strong hedgerow

positions with interlocking fields of machine gun fire and mortar coverage.[3]

|

| Mortars of Company E, 121st Infantry Regiment were positioned here in the vicinity Montsenelle-Lithaire July 8, 1944. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

Consolidating under the cover of darkness, the 1st and

2nd Battalions continued to advance through the morning of July 9, gaining another

200 yards of ground. In just one day’s combat, 1st Battalion had lost fifty

percent of its combat strength. Nevertheless, the 121st continued its advance

through the afternoon with the 3rd Battalion driving forward 500 yards while

sustaining heavy casualties. Artillery fire, and flanking fire from the 90th

Division supported 3rd Battalion’s advance while enemy counterattacks pummeled

1st and 2nd Battalion. Morrison was killed and command of the 2nd Battalion

fell to Maj. James Mallory who was killed in subsequent action. Mallory was

succeeded by Lt. Col. Augustine Dugan who was himself wounded in action.[4]

While the troops had paid a heavy price for the ground

gained, their efforts had not satisfied the expectations of higher command. Blame

for the slow progress was placed at the feet of the 8th Division commander

whose troops were encountering the enemy for the first time. In short order,

the division commander was relieved as were two regimental commanders including

Col. Albert Peyton of the 121st. Brigadier General Nelson Walker, assistant

commander of the 8th Infantry Division communicated the changes to the 121st

command post and helped to reorganize the advance. Departing the CP, Walker was

crossing a hedgerow when he was caught by machine gun fire. Medics from 2nd

Battalion moved under fire to aid the fallen general despite his insistence

that the men not risk themselves. Private Philip Weintraub was hit en route, but

Cpl. Alfred Michaud was able to reach the mortally wounded Walker and drag him

to safety before returning to evacuate three more Soldiers.

The new regimental commander of the 121st, Col. John

Jeter, continued to direct his battalions forward in the face of punishing

enemy resistance. [5]

Jumping off at 8:00 am, 2nd Battalion reached its initial objective 80 minutes

later. The 2nd Battalion, augmented by tank destroyers and supported by 1st Battalion

continued the advance with coordinated artillery and mortar fires. The

southeast axis of advance by the 2nd Battalion was disrupted by fields of teller

mines which stalled the advance.

|

| Minefields encountered by 2nd Battalion 121st infantry Regiment July 10, 1944. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

The 121st consolidated its gains overnight and into the morning hours of July 11. The regiment began moving southeast at 6:00 across the bocage towards a prominence identified on maps as Hill 112, though Soldiers of the regiment would recall it as Purple Heart Hill. Lead elements of 2nd Battalion spotted pill boxes protecting the approach to the hill. As the day wore on, 1st Battalion assumed the advance with 2nd Battalion moving into reserve. Splashing across a creek, the 1st Battalion took fire from German artillery. Jones was killed by shrapnel as his men surged to the base of Hill 112. Assuming command of the battalion, Maj. Joel Hollis of Atlanta directed his troops in the surge over and around Hill 112.

|

| Stream crossed by 1st Battalion, 121st Infantry Regiment July 9, 1944, on approach to Purple Heart Hill. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

At 6:15 the morning of July 12, 1st and 3rd Battalion advanced

taking position 1,200 yards in front of Hill 112. The regiment had taken the

key terrain after five days of intense close-quarter combat. By July 12, the

regimental surgeon had reported 402 medical evacuations, which is a staggering

number by itself, but does not represent the full account of casualties

suffered by the 121st in less than a week on Normandy’s soil. Hollis was

wounded by shrapnel on July 12 during the advance from Hill 112 towards Hill 92.

He had been in command of 1st Battalion for just over 18 hours when he was

evacuated.

|

| Purple Heart Hill in July 2023. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

The ferocity of the action in the vicinity of La Haye du

Puits is written in the blood of those who fell. In five days of combat, 26

Georgia National Guard Soldiers were killed in action. The regiment lost five

battalion commanders killed or wounded. The action was also replete with

individual acts of valor. Michaud and Weintraub were awarded the Silver Star

for their efforts to save wounded soldiers, including Brig. Gen. Walker. Captain

William McKenna, a native of Macon, Ga. also received the Silver Star for rallying

Soldiers of 2nd Battalion and leading them to restore a battle line. In this

action, McKenna single handedly destroyed an enemy strongpoint with hand grenades.[6]

|

| Monument honoring Lt. Col. Forgy and the 121st Infantry Regiment. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

Incredibly, Hill 112 did not mark the end of intense combat for the 121st which continued its advance southeast towards St. Patrice de Claids, suffering an additional 300 casualties July 13 and 14. Casualties continued to mount as the 121st clawed its way to the Ay River. Among the fallen was Major Albert Hudson, commanding 2nd Battalion, who was mortally wounded July 16 and Lt. Col. Percy Forgy who was killed in action July 27, 1944, while leading 2nd Battalion in action near St. Patrice de Claids.

In just over one week of combat, more than 500 of the Soldiers of the 121st who waded ashore on Utah beach had fallen in the approach to Purple Heart Hill. The 121st would fight on, through Brittany to Dinard and Brest along the coast and on the Hurtgen forest, where the regiment would receive the Presidential Unit Citation. Eighty years later, the 121st Infantry Regiment is deployed overseas supporting combat operations in the Central Command area of operations.

[1]

The Gray Bonnet: Combat History of the 121st Infantry. Baton Rouge, LA:

Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1946, 18.

[2]

Martin Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, Washington, D.C.: Office of the

Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army, 1961, 124.

[3]

The Gray Bonnet: Combat History of the 121st Infantry. Baton Rouge, LA:

Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1946, 27.

[4]

The Gray Bonnet: Combat History of the 121st Infantry. Baton Rouge, LA: Army

& Navy Publishing Company, 1946, 29.

[5]

Martin Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit, Washington, D.C.: Office of the

Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army, 1961, 125.

[6]

The Gray Bonnet: Combat History of the 121st Infantry. Baton Rouge, LA:

Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1946, 30.

No comments:

Post a Comment