Historian, Georgia Army National Guard

|

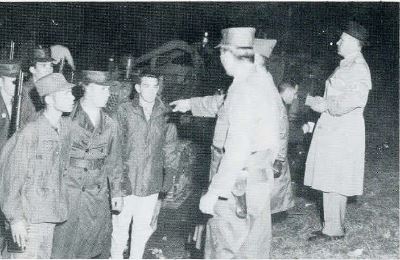

| Captain William McKenna (pictured in 1939) was twice awarded the Silver Star Medal for his actions while leading Soldiers of the 121st Infantry Regiment in combat during World War II. |

Early Life

William Andrew McKenna was born in Macon, in 1910[1] to first generation Irish Americans William and Mary McKenna. The elder William worked as a bookkeeper in a jeweler’s store while Mary tended to seven children of which young William Andrew was the third.[2]

In May 1927, McKenna joined the local National Guard company, the famed Floyd Rifles, which had served in the 151st Machine Gun Battalion in World War I. Though still in high school McKenna took to Soldiering quickly and was promoted to private 1st class.

|

| The 151st Machine Gun Battalion in France in 1917. Georgia Guard Archives. |

Preparing for War

|

| First Lieutenant William McKenna in 1941. Georgia National Guard Archives |

McKenna rose through the enlisted ranks and by May 1939 was first sergeant of Company F. In November he was commissioned a second lieutenant. On September 16, 1940, he was accepted into federal service with Company F and the 121st Infantry Regiment and dispatched to Fort Jackson S.C. for sixteen weeks of initial training. On December 26, 1940, McKenna married Ms. Cecile Cassidy during a ceremony at St. Joseph’s Church in Macon.

McKenna was promoted to 1st lieutenant March 14, 1941, and two months later, the 121st participated in the Tennessee Maneuvers followed by the Carolina Maneuvers. In the fall of 1941, the 121st was transferred from the 30th Division to the 8th Infantry Division.

McKenna participated in the grueling train up through the Second Army Maneuvers in Tennessee to the Desert Training Center in Yuma Arizona. He displayed impressive leadership qualities and was promoted to captain August 22, 1942. Finally, on November 25, 1943, McKenna, and the Soldiers of the 121st boarded a train bound for Camp Kilmer, N.J. before embarking from Brooklyn, N.Y. aboard the U.S.S. Beanville and Columbia. While at sea, McKenna confided that he had a suspicion that he would never return to the United States.[4]

After a ten-day voyage, the Gray Bonnets arrived in Belfast Harbor. Over the next six and a half months, the 121st conducted field problems and combat training in anticipation for the Normandy invasion.

Normandy

On July 4, the first Soldiers of the Gray Bonnet Regiment splashed ashore on Utah Beach. Upon landing and consolidating, the 121st was dispatched south to La Haye du Puits where the U.S. VIII Corps was attempting to dislodge German forces and advance out of the swampy lowland terrain. Arriving on July 8, the 8th Division was assigned as the main effort of the attack which would strike a narrow front between Lessay and Perriers.

|

| La Haye du Puits, France in 2023. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

During the heavy fighting, McKenna led companies of the 2nd Battalion forward to reestablish contact with 3rd Battalion. Surveying the enemy line, McKenna perceived that hostile fire had ceased from a sector and moved forward to investigate. McKenna advanced to a hedgerow which concealed a considerable force of German troops. Calling loudly for their surrender, McKenna was rebuffed when the German commander ordered his Soldiers to open fire. Calmly, McKenna secured a string of hand grenades and continued to advance within a few yards of the enemy where he destroyed the German strong point with hand grenades. For his actions, McKenna was awarded the Purple Heart and Silver Star.[5]

|

| Soldiers of the 121st Infantry move through the ruins of Hurtgen, Germany in December 1944. National Archives. |

McKenna fought with the 121st Infantry Regiment through Normandy and the successive Brittany Campaign. He endured savage fighting in the Hurtgen Forest and by December 1944 was leading Company B in the attack on Obermaubach, a German town that overlooked a dam on the Roer River.

|

| Position of Company B, 121st Infantry Regiment on December 24, 1944, just north of Obermaubach, Germany. Photo by Maj. William Carraway |

On Christmas Day, 1944, McKenna was characteristically leading his men from the front, crawling ahead of the company, and reporting the positions of machine gun positions for artillery. McKenna remained thus exposed until machine gun fire compelled him to return to Company B’s fighting positions just as his company was receiving a heavy artillery barrage. Ignoring the incoming fire that split fir trees and caused geysers of frozen earth to erupt around him, McKenna moved among his men’s fighting positions encouraging them to maintain their fire. When the enemy artillery fire slackened, McKenna once again moved to the front of his men to direct a counterattack. He was out in front of his company when he was killed by small arms fire.

On October 23, 1960, an armory was dedicated in honor of Capt. William McKenna in his hometown of Macon.